Interview with Katy Derbyshire, literary translator

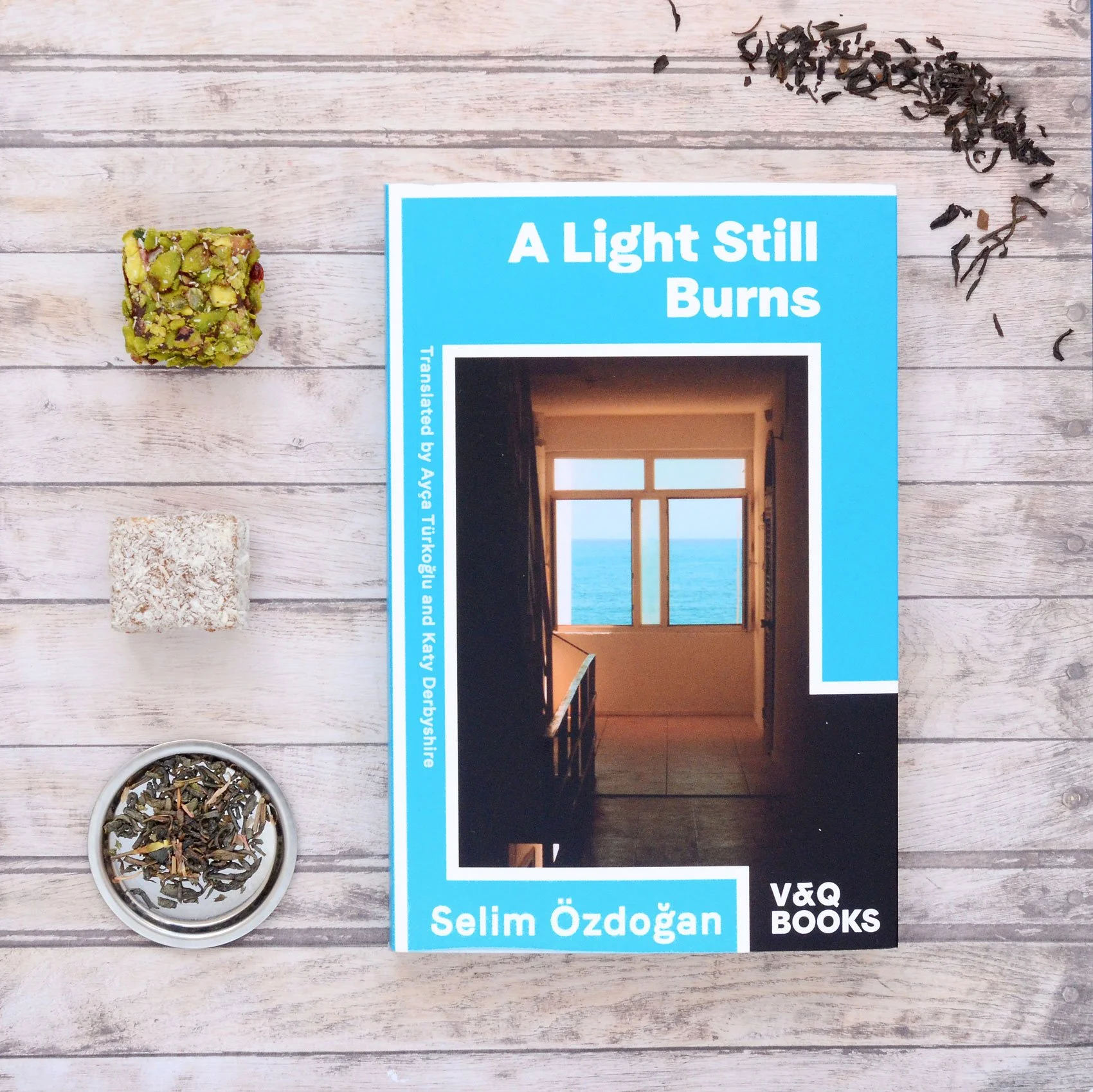

As the third volume in Selim Özdoğan’s Anatolian Blues trilogy hits the shelves this week, literary translator and publisher Katy Derbyshire talked to me about translating, homesickness, and how fiction explores the topics people don’t talk about.

Gül lives in an attic above a bookshop and watches the street from her window. She’s got nothing to do and no one to talk to. She’s a Turk in Germany, nursing her wrath against her cheating husband. She smokes and swears and observes the drug deals and hustlers at work below. Eventually she’ll befriend one . . .

Let’s set the scene with your workspace, Katy. What reference tools do you always have to hand, and do you use the same desk for translating as for publishing?

I have three desks at the moment: one in the V&Q Books office chez Voland & Quist, one at home, and one in an office share. The idea is definitely to separate my publisher and translator roles, and also keep my private life apart from work, which doesn’t always work . . . So the only things always on my desk when I translate are a cup of green tea with lemon, my laptop, a pencil and my trusty paper diary.

I use a couple of online dictionaries, especially dict.cc, which is partly crowd-sourced and very trustworthy, and I have a lot of physical books in the office. Things like a picture dictionary, specialised reference works for police business or musical terms, a thesaurus, a dictionary of clichés, a nursery-rhyme collection – they’re all useful because they make me stop typing and think for a moment.

In A Light Still Burns, protagonist Gül feels estranged from her Turkish homeland. As someone who has also moved from your motherland to Germany, how much do you see yourself in Gül? Do you share her sense of homesickness?

I think my decision to come to Germany was much more self-determined than Gül’s - she followed her husband to an unknown country to earn money for a few years, and ended up staying. Whereas I already spoke German when I moved here, having studied it at university. I’d spent a lot of time in Berlin beforehand and I knew people here, but I was only 23 and I didn’t have a plan for my life. I don’t remember thinking about how long I’d stay – I was pretty carefree and clueless.

Nonetheless, there are lots of things I can relate to – missing certain foods, and of course people. The world’s changed so much, as we see in the novel; now I can talk to my mum and sister whenever it suits us, wherever we are, unlike in Gül’s early days when no one had a phone.

“I suppose I’m homesick for a place that no longer exists – another problem Gül comes up against.”

“Those who leave can never return, because the places they knew disappear.”

I’ve been in Germany so long that I rarely feel homesick now, but it is very strange and painful watching what Brexit is doing to the country where my family lives. The referendum result felt like a rejection of everything I’ve done in my life, which was only possible because of freedom of movement. Hence the burning need to start up V&Q Books, incidentally. I suppose I’m homesick for a place that no longer exists – another problem Gül comes up against, as Turkey becomes a different country to the one she left behind.

While Gül’s father, the blacksmith Timur, doesn’t think much of German bread, he does observe that the country appears ‘freshly washed and ironed.’ How is your experience of Germany shaped by what you read?

What a great question! A huge amount, I suspect. As I mentioned earlier, I studied German in the UK and we learned about German history. But reading fiction has given me a much deeper understanding of the emotional impact of those events – from the Nazi era as in Julia Franck’s excellent The Blind Side of the Heart (tr. Anthea Bell) to the experience of migration, as in Selim’s books.

“...there’s no point pretending a book’s not translated.”

Another example is the Chernobyl disaster: a number of German writers have addressed the way young children experienced it in West Germany. Their parents were terrified and wouldn’t let them go outside, but the children themselves were mystified, couldn’t understand why their lives changed so suddenly. There are things people don’t necessarily talk about in everyday life, whereas reading fiction has opened my eyes to them and helped me relate to the country.

I agree with Timur about the ‘freshly washed and ironed’ look of West Germany, by the way – one reason why I live in Berlin, which is a city that’s been through the mangle so many times that it’s very rough and crinkled.

Katy Derbyshire © Nane Diehl

What initially drew you to the Anatolian Blues trilogy?

I was initially drawn to the first book, The Blacksmith’s Daughter, way back when it came out in 2005. What I loved about it was the calm, affectionate narration, coupled with the glimpses of the future we get throughout the novel. I loved its premise: what lives did people lead before they became migrant workers, who were the people who were so often lumped together as ‘guest workers’, anonymous faces in a crowd? And with each new book in the trilogy, I came to love the characters more.

There are so many scenes that have stayed vivid in my mind. In A Light Still Burns, Timur visits Bremen; he and Gül are so happy to be together, but the tables are now turned. She worries about her father getting lost in the big city – but he goes out walking, discovers a whole new part of the neighbourhood and makes a new friend. It says so much about the characters and I can also relate to it very well, from my mum’s visits to Berlin.

How did you divide the project with co-translator Ayça Türkoğlu? Did your work process together change over the course of the three novels?

“There’s no going back, and you can’t just up and leave and find a new homeland because you weren’t happy with the old one.”

Since all three books have a similar anecdote-like structure, we divided each one into short sections and translated alternating parts, editing each other’s work on a rolling basis. That way, we had a good sense of continuity, with a constant conversation going on in the margins.

I think what changed is that both of us relaxed into co-translating as we went along. We both got more confident about the process, happier to raise questions but also more and more admiring of each other’s work – or that’s how I felt, anyway. It’s a sad feeling to have finished the project, having devoted three summers in a row to working with Ayça. It’s made us great friends, though.

Do you remember when you first met Selim Özdoğan? How involved was he in the translation process?

I think we first met at one of his amazing readings in Berlin; he’s incredibly entertaining on stage. It will have been around 2005 because The Blacksmith’s Daughter was the first of his many great books that I read. We must have got chatting and stayed in touch, and I’ve been to a lot of Selim’s events in Berlin since then. I tried very hard indeed to find a UK publisher for the novel at the time, and failed, so bringing the trilogy out with V&Q Books has been a very personal mission.

He was always an email away when Ayça and I had any questions; we’d usually flag things up in our manuscript and ask him if neither of us had an answer – what kind of underwear do women wear in the Black Sea region, did he have a particular song in mind here, is there a Turkish saying hiding away in this phrase – that kind of thing. Very helpful!

When literature is your world, how do you separate work from leisure? Do you still read for fun?

That’s another good question, and the answer is that it’s hard to separate work reading from leisure reading – but both are still a source of great joy. Sometimes I’ll start a book thinking it’s just for fun, and then I get so into it I hope it’ll become work reading.

“Affording translators the respect of naming them on the cover is an easy way to make us visible.”

Reading in English is easier (no potential for translation) but there are still times when I’ll draw something from a book for my work – what can we get away with in English, how beautifully flexible the language is. I remember a scene in Sarah Perry’s The Essex Serpent where two characters in Victorian England agree to switch from surnames to first-name terms. German still makes that distinction very clearly and it’s hard to translate those situations, and there I had it on a plate!

That is interesting. I’ll quiz you more about that next time. But for today, one final question: not all publishers put the translator’s name on the cover. Should they?

Yes! It costs nothing and there’s no point pretending a book’s not translated. I like to think people either don’t care, or are really turned on by the fact that a book’s translated. Think of all those people who stay seated in the cinema for the credits, to see who designed the costumes or wrote the score or trained the dogs. Affording translators the respect of naming them on the cover is an easy way to make us visible.

Thank you very much Katy!

A Light Still Burns is the third in Selim Özdoğan’s Anatolian Blues trilogy and is preceded by The Blacksmith’s Daughter and 52 Factory Lane. All three were originally written in German and translated into English by Katy Derbyshire and Ayça Türkoğlu.

WHAT TO READ NEXT

Literary translator Sinéad Crowe discusses the tricks of the translator’s trade and Lucy Fricke’s novel Daughters.

Shortlisted for the 2017 Man Booker International Prize, Roy Jacobsen’s The Unseen is the refreshing and subtle portrait of Ingrid Barrøy and the hardscrabble island she makes a life from; translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw.